Check out my first novel, midnight's simulacra!

Daytripper: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

* No Length-Changing Prefix penalties, as the pre-decode stage has already been passed | * No Length-Changing Prefix penalties, as the pre-decode stage has already been passed | ||

* Reduced front end power consumption, because the instruction cache, BPU and predecode unit can be idle | * Reduced front end power consumption, because the instruction cache, BPU and predecode unit can be idle | ||

Source code can be found at http://github.com/dankamongmen/wdp/tree/master/cs8803dc-project/. An initial writeup is available [[media:Cs8803dcproject.pdf|here]]. | |||

==Loop Stream Detector== | ==Loop Stream Detector== | ||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

* LSD.UOPS: [[Performance Counters|performance counter]] providing the number of μops delivered by the LSD (introduced on Core i7) | * LSD.UOPS: [[Performance Counters|performance counter]] providing the number of μops delivered by the LSD (introduced on Core i7) | ||

* David Kanter had some [http://realworldtech.com/page.cfm?ArticleID=RWT040208182719 excellent insight]:<blockquote>One of the most interesting things to note about Nehalem is that the LSD is conceptually very similar to a trace cache. The goal of the trace cache was to store decoded uops in dynamic program order, instead of the static compiler ordered x86 instructions stored in the instruction cache, thereby removing the decoder and branch predictor from the critical path and enabling multiple basic blocks to be fetched at once. The problem with the trace cache in the P4 was that it was extremely fragile; when the trace cache missed, it would decode instructions one by one. The hit rate for a normal instruction cache is well above 90%. The trace cache hit rate was extraordinarily low by those standards, rarely exceeding 80% and easily getting as low as 50-60%. In other words, 40-50% of the time, the P4 was behaving exactly like a single issue microprocessor, rather than taking full advantage of [its] execution resources. The LSD buffer achieves almost all the same goals as a trace cache, and when it doesn’t work (i.e. the loop is too big) there are no extremely painful downsides as there were with the P4's trace cache.</blockquote> | * David Kanter had some [http://realworldtech.com/page.cfm?ArticleID=RWT040208182719 excellent insight]:<blockquote>One of the most interesting things to note about Nehalem is that the LSD is conceptually very similar to a trace cache. The goal of the trace cache was to store decoded uops in dynamic program order, instead of the static compiler ordered x86 instructions stored in the instruction cache, thereby removing the decoder and branch predictor from the critical path and enabling multiple basic blocks to be fetched at once. The problem with the trace cache in the P4 was that it was extremely fragile; when the trace cache missed, it would decode instructions one by one. The hit rate for a normal instruction cache is well above 90%. The trace cache hit rate was extraordinarily low by those standards, rarely exceeding 80% and easily getting as low as 50-60%. In other words, 40-50% of the time, the P4 was behaving exactly like a single issue microprocessor, rather than taking full advantage of [its] execution resources. The LSD buffer achieves almost all the same goals as a trace cache, and when it doesn’t work (i.e. the loop is too big) there are no extremely painful downsides as there were with the P4's trace cache.</blockquote> | ||

* [[Ivy Bridge]] allows one logical core to use the full 56-μops cache if the other core is inactive | |||

===Constraints=== | ===Constraints=== | ||

The Loop Stream Detector requires a number of properties from any loop hoping to be cached... | The Loop Stream Detector requires a number of properties from any loop hoping to be cached... | ||

| Line 32: | Line 34: | ||

** address size prefix (0x67) | ** address size prefix (0x67) | ||

* Binary translation framework candidates: [http://dynamorio.org DynamoRIO], [http://valgrind.org Valgrind], see [[#History|below]] | * Binary translation framework candidates: [http://dynamorio.org DynamoRIO], [http://valgrind.org Valgrind], see [[#History|below]] | ||

===Size Reductions=== | |||

* remove alignment NOPs (since there are no alignment penalties in LSD-supplied code) | |||

* add/sub 0x1 -> inc/dec | |||

* magic division -> division by constant | |||

* multiple push/pop pairs -> pusha/popa | |||

===Milestones=== | ===Milestones=== | ||

* Proof-of-concept: | * Proof-of-concept: | ||

| Line 49: | Line 56: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

* daytripper began as a project for Nate Clark's spring 2010 CS8803DC, "Dynamic Translation and Virtual Runtimes" at the Georgia Institute of Technology. | * daytripper began as a project for Nate Clark's spring 2010 CS8803DC, "Dynamic Translation and Virtual Runtimes" at the Georgia Institute of Technology. | ||

** [[media:Cs8803dcproject.pdf|Final project submission]] | |||

* some early notes on [[CybOregonizer|binary translation]] | * some early notes on [[CybOregonizer|binary translation]] | ||

| Line 55: | Line 63: | ||

* Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Optimization Reference Manual (Order № 248966-018), March 2009. §2.1.2.3 and 3.4.2.4. | * Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Optimization Reference Manual (Order № 248966-018), March 2009. §2.1.2.3 and 3.4.2.4. | ||

* Dickson, Neil G. "[http://arxiv.org/pdf/0812.4973 A Simple, Linear-Time Algorithm for x86 Jump Encoding]". 2008-12-25. | * Dickson, Neil G. "[http://arxiv.org/pdf/0812.4973 A Simple, Linear-Time Algorithm for x86 Jump Encoding]". 2008-12-25. | ||

* Agner Fog's [http://www.agner.org/optimize/ instruction tables] provide instruction->µop mappings | |||

[[Category: x86]] | [[Category: x86]] | ||

[[Category: Projects]] | [[Category: Projects]] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:39, 2 May 2013

daytripper analyzes and rewrites binaries to better take advantage of Intel's Loop Stream Detector (LSD). The result ought realize power savings (by reducing the amount of computation performed, and allowing the frontend to be powered down) and some performance benefit (due to avoiding instruction fetch limitations). The 2009-03 edition of Intel's Optimization Reference Manual claims the following benefits:

- No loss of bandwidth due to taken branches

- No loss of bandwidth due to misaligned instructions

- No Length-Changing Prefix penalties, as the pre-decode stage has already been passed

- Reduced front end power consumption, because the instruction cache, BPU and predecode unit can be idle

Source code can be found at http://github.com/dankamongmen/wdp/tree/master/cs8803dc-project/. An initial writeup is available here.

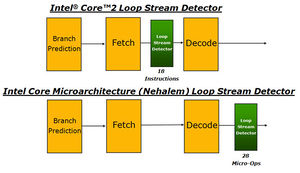

Loop Stream Detector

- Lives in the branch prediction unit

- Introduced in Conroe (followed instruction fetch, supporting 18 x86 instructions)

- Improved in Nehalem (moved after decode, caching 28 decoded μops)

- LSD.UOPS: performance counter providing the number of μops delivered by the LSD (introduced on Core i7)

- David Kanter had some excellent insight:

One of the most interesting things to note about Nehalem is that the LSD is conceptually very similar to a trace cache. The goal of the trace cache was to store decoded uops in dynamic program order, instead of the static compiler ordered x86 instructions stored in the instruction cache, thereby removing the decoder and branch predictor from the critical path and enabling multiple basic blocks to be fetched at once. The problem with the trace cache in the P4 was that it was extremely fragile; when the trace cache missed, it would decode instructions one by one. The hit rate for a normal instruction cache is well above 90%. The trace cache hit rate was extraordinarily low by those standards, rarely exceeding 80% and easily getting as low as 50-60%. In other words, 40-50% of the time, the P4 was behaving exactly like a single issue microprocessor, rather than taking full advantage of [its] execution resources. The LSD buffer achieves almost all the same goals as a trace cache, and when it doesn’t work (i.e. the loop is too big) there are no extremely painful downsides as there were with the P4's trace cache.

- Ivy Bridge allows one logical core to use the full 56-μops cache if the other core is inactive

Constraints

The Loop Stream Detector requires a number of properties from any loop hoping to be cached...

Pre-Nehalem

- No more than 18 instructions, none of them a CALL

- Requires no more than 4 decoder fetches (16 bytes each)

- No more than 4 branches, none of them a RET

- Executed more than 64 times

Nehalem

- No more than 28 μops

Methodology

- Start with innermost loops only, though the approach ought work for all loops.

- Identify loops the same way the LSD (presumably) does: watch for a short branch backwards

- Remember, it lives in the branch prediction unit!

- LCP stalls with loops will be eliminated by Nehalem's LSD, augmenting the optimization. These include:

- operand size prefix (0x66)

- address size prefix (0x67)

- Binary translation framework candidates: DynamoRIO, Valgrind, see below

Size Reductions

- remove alignment NOPs (since there are no alignment penalties in LSD-supplied code)

- add/sub 0x1 -> inc/dec

- magic division -> division by constant

- multiple push/pop pairs -> pusha/popa

Milestones

- Proof-of-concept:

Complications

- Don't allow "gratuitous" LCP stalls to cloud benchmarks

- Perhaps we ought also rewrite to remove LCP stalls? LCP stalls have been known about for a long time. It's doubtful that many "gratuitous" ones exist.

- An innermost loop might not be a basic block. Exits in media res and oddly-encoded loop conditionals might violate the single-exit condition.

- Most binary translation frameworks seem to work on basic blocks

- Furthermore, jumps/branches elsewhere might violate the single-entry condition.

- The presence of indirect branches greatly complicates matters! Can't even perform a runtime fixup (if we wanted to)

- We probably can't safely rewrite in the presence of arbitrary indirect jumps.

- At what scope? Function containing the loop? Binary? Linked binary?

- Might, say, ELF specifications contraindicate jumps into an object other than at exported points?

- Indirect jumps (modulo returns) are presumably rare within a given function body(?)

- Even if we wrote our replacement elsewhere in the binary, and shimmed it in the inline sequence, and somehow still improved performance, there might be an indirect jump into whatever code the shim itself replaced. We'll likely need to rely on the binary translation framework's capability (and the binary's amenability) to jump target disambiguation.

- At what scope? Function containing the loop? Binary? Linked binary?

History

- daytripper began as a project for Nate Clark's spring 2010 CS8803DC, "Dynamic Translation and Virtual Runtimes" at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

- some early notes on binary translation

See Also

- Real World Technologies article, "Inside Nehalem: Intel's Future Processor and System". 2008-04-02.

- Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Optimization Reference Manual (Order № 248966-018), March 2009. §2.1.2.3 and 3.4.2.4.

- Dickson, Neil G. "A Simple, Linear-Time Algorithm for x86 Jump Encoding". 2008-12-25.

- Agner Fog's instruction tables provide instruction->µop mappings